This slice of Napa Valley resisted the region’s luxury boom — until now

Read the full article here.

By Jess Lander | The San Francisco Chronicle

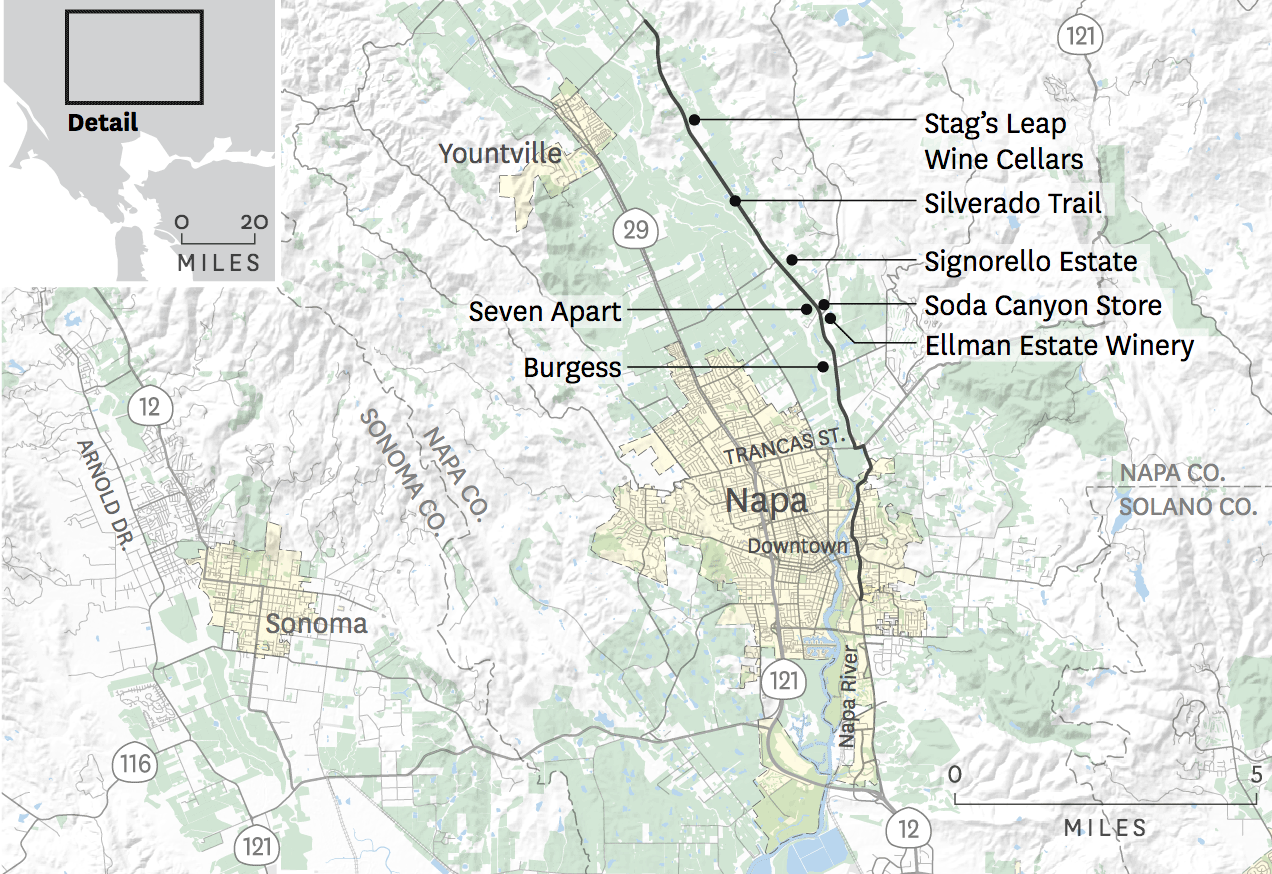

The south end of Napa Valley’s scenic Silverado Trail is a rustic snapshot of the region 30 years ago, a simpler era reflected in the locally famous strawberry stand, a small family farm, and an old-timey general store and deli. There’s still evidence of the cattle and horse ranches that preceded the vines spanning Napa to Calistoga.

Along those first 3 miles of the 30-mile highway — one of the region’s two major thoroughfares — it’s almost as if Napa Valley’s dramatic transformation from a quiet farming community to a luxury tourist destination never happened. But over the past four years, that’s started to change: The Soda Canyon Store, a Napa landmark dating back to 1946, inexplicably closed last year, and several glitzy, high-end wineries have popped up between the handful of modest wineries that have occupied this stretch of road for decades.

The metamorphosis of the Silverado Trail’s gateway might have seemed inevitable as affluence has proliferated throughout Napa Valley over the past decade, and given the ongoing redevelopment of downtown Napa 2 miles south. But this quaint pocket of Wine Country is also being recognized for the kind of wine that it’s able to produce. “Top talent is starting to turn their eyes here,” said Yannick Girardo, managing partner at Seven Apart, a swanky boutique winery that sells wines for as much as $450 a bottle. It opened kitty-corner to the Soda Canyon Store at the end of 2021.

For decades, anyone pulling over at the intersection of Soda Canyon Road was likely stopping at the store — the lone spot on the entire Silverado Trail to grab coffee or a casual lunch — which was family-owned for most of its existence. Now they’re likely visiting Ellman, Napa Valley’s newest winery, which opened directly across from the shuttered store in September. The wines, priced between $125 and $350 a bottle, are made by famed Napa winemaking consultant Andy Erickson. The sleek tasting room features dramatic vineyard views, a striking rhino statue, collectible art, a record player and custom furnishings. Tastings cost $175, not unusual in Napa these days.

“We wanted a hedonistic, comfortable vibe, for you to come in and feel like you’re in your own living room,” said Neil Ellman, who co-founded the winery with his brother Lance. The brothers, born in South Africa — hence the rhino — are also third-generation mattress manufacturers. “We’ll spin vinyl and you’ll drink world-class wines.”

Further south, the billionaire-backed Lawrence Wine Estates opened its elegant new home for Burgess Cellars, one of Napa Valley’s most classic wineries, in 2023. The dreamy, Provençal-inspired estate hosts a speakeasy behind a bookshelf door. Two miles north, Signorello, which burned to the ground in the 2017 wildfires, unveiled its rebuild last year: a splashy, 20,000-square-foot facility complete with caves. It’s four times the size of Signorello’s original, more understated winery.

The barrel room at the swanky Seven Apart, which opened at the end of 2021 on the south end of the Silverado Trail.

Prior to these developments, the wineries along this stretch of the Silverado Trail toiled in the shadow of their revered neighbor immediately to the north, the Stags Leap District, home to some of Napa’s most illustrious Cabernet Producers, such as Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, Shafer and Clos du Val. South of Stags Leap, the majority of the Silverado Trail wineries are humble, under-the-radar family operations, like Judd’s Hill, Hagafen and Reynolds Family, which all offer tastings for $50 or less. There were only two in the area that could accommodate more than two dozen visitors at once: the corporate-owned Black Stallion and Darioush, modeled after the ancient Persian city of Persepolis.

Judd Finkelstein, owner of Judd’s Hill, which moved to the south end of the Silverado Trail in 2005, feels the area has been undervalued due to “marketing,” or lack thereof, compared to Napa sub-regions further north, like Stags Leap, that “throw a little something into their PR.”

Wineries on the southwest side of the Silverado Trail, such as Seven Apart and Burgess, just barely fall within the eastern border of the Oak Knoll District, one of Napa Valley’s lesser-known subregions. The southeast side of the highway, where Judd’s Hill, Ellman and Signorello are located, is a sort of no-man’s land, left out entirely from Napa Valley’s 17 federally designated appellations. This can disadvantage wineries; instead of utilizing a prestigious subregion like Oakville or Stags Leap on their label (often associated with high quality), wines made from their estates simply read “Napa Valley.”

This end of the Silverado Trail “has retained its ‘old Napa’ charm for a long time,” said Finkelstein. “For two decades, we were the new folks on the block down there. With the challenges we’ve been facing in the wine business for the past couple of years, it’s been pretty tough. So I’d say any excitement, any draw for visitation, I welcome it.”

When Ray Signorello Jr. purchased his hillside property, a former horse ranch, in the 1970s, people thought the area “was too cool temperature-wise” to grow Cabernet. The first grape he planted was Chardonnay, but today, “it’s all Cabernet in our area,” he said. And now, cooler-climate red wines are trending: Consumers are shifting away from the stereotypical ripe, Napa fruit bomb and seeking out more classic styles — high in acid, restrained and lower in alcohol — from cooler regions like Sonoma County’s Moon Mountain, which foster those characteristics. =

“On really hot days,” Seven Apart winemaker Morgan Maureze said it can be “5 to 10 degrees” cooler in southeast Napa than subregions further north. Maureze apprenticed under consultant Erickson at some of Napa’s most exclusive estates, including Oakville’s Screaming Eagle and Dalla Valle.

Tourists are discovering it, too. “Something is definitely brewing,” said Maureze. “I think people just never really looked at this area.”

Most used to bypass Napa for chef Thomas Keller’s hub of Yountville, 9 miles north; now, the majority anchor in the buzzy downtown, where there are several large hotels and more in development. When Signorello Jr. opened his winery, “the town of Napa was not really much,” he said. But now, it’s “the epicenter” of the region.

Stanly Ranch, a 700-acre luxury resort that opened in south Napa in 2022, attracts the kind of clientele sought by wineries like Ellman and Seven Apart. Rooms typically start at $1,000 a night. “You’re getting a whole new crowd that’s staying south of (the Silverado Trail),” Neil Ellman said.

Still, Signorello Jr. doesn’t expect the area around his estate to change much more. As he learned firsthand after his winery burned down, it’s become extremely difficult — and expensive — to obtain a winery permit in Napa County. Permits cost roughly $22,000 on average, sometimes as much as $100,000, and can take years to be approved.

“I’s been quite an ordeal,” said Signorello Jr. “A lot of people would be thinking twice about rebuilding a winery or building a new winery given the immense costs of construction, the headwinds of permitting and the headwinds of the wine industry right now.”

The Ellmans, who purchased their estate in 2015, can relate. It was 10 years before they finally opened, largely due to permitting delays. “It was a roller coaster,” Neil Ellman said. “We really had to hold our own until this was done.”

But the brothers believe the wait was worth it.

“This is not a vanity project for us. It’s not a five-year return on investment,” he said. “This is a generational play.”